Text by Ela Kagel, commissioned and published by Berliner Gazette, in May 2023

If every economic activity has an ecological footprint, then it is obvious that we, as workers in a capitalist economy, have a significant share in climate production – largely unconsciously. In her contribution to the BG text series “Allied Grounds,” author and curator Ela Kagel reflects on how work can be organized as conscious and at the same time sustainable climate production.

*

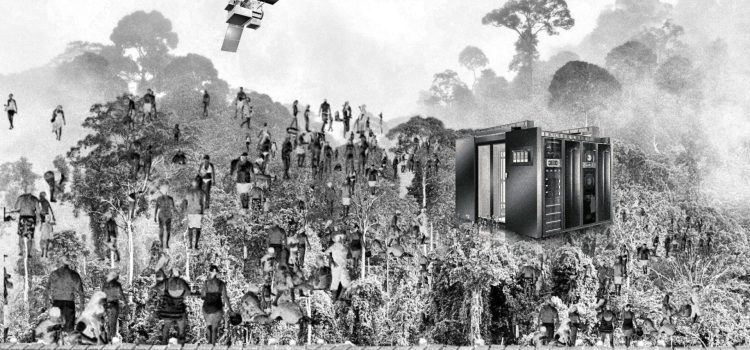

In the introduction to “Allied Grounds,” Magdalena Taube and Krystian Woznicki, co-editors of the Berliner Gazette (BG), write: “The means of production have become the means of climate production. So how can we – all kinds of exploited workers around the world – seize these very means and address both the ecosocial and decolonial questions of the climate crisis?”

In this article, I will try to answer this question from the perspective of reorganization, and bring new questions to the center: How can the workplace become a site of resistance to capitalist exploitation and climate destruction? How can new structures of (collective) self-organization emerge? And how is it possible not only for a few to work “better” and “more sustainably,” but for everyone?

First, it is important to understand the relationship between work and climate production. Traditional gainful employment generates emissions – in all occupations. It doesn’t matter whether it’s industry, office work, hospitals, kindergartens or restaurants. Everywhere, people drive, deliver, heat and cool, and use technical equipment and digital infrastructure. All of this generates emissions from energy production and use.

Work, at least as it is organized today, is harmful to the climate. In fact, this can be measured quite accurately: Based on the resulting carbon intensity, it is possible to calculate how much greenhouse gas emissions are generated per unit of economic output and how many emissions are contained in an hour of work. The calculation is sobering: Instead of the usual 40-hour work week, a maximum of 9 hours per week would be indicated.

Working differently, working much less or not at all, means appropriating the means of climate production. But how does this relate to a labor market conditioned by war, pandemic, inflation, and artificial intelligence, and to the all-encompassing dogma of work and performance that at least pre-millennials in the Global North grew up with?

Can we reorganize work?

To reorganize the global workload to be at least somewhat more sustainable, it would also have to be made more socially just and removed from the profit motive. This would require a comprehensive global alliance in the areas of circular economy, waste management, sustainable transportation, remote work, local food production, data saving programs, and extensive education and awareness-raising. It will take the cooperation of all countries, all governments, all businesses, and all people to make the transition to a sustainable future possible. No more and no less.

In order not to lose the desire to think further under the weight of this idea, we will now look at different scenarios for reorganizing work. An overview of measures that are within the realm of possibility: Giving up traditional employment, receiving a basic income, or organizing work through commons-based enterprises or platform cooperatives. The sustainable work of the future could be characterized by all of these approaches.

Get paid for doing nothing?

As part of BG’s annual conference After Extractivism, I co-facilitated the Climate & Tech Politics workshop. Together we developed the Protocol of Planned Disconnect, a collection of current policies and fictional news stories from a not-too-distant future of complete digital disconnection. Among other things, it lists the following emergency policy actions from 2035:

Internet abstinence rewarded with EUR 100 per day!

In a desperate attempt to reduce energy consumption, the German Federal Ministry for the Environment and the Digital Ministry have launched a pilot project in which Internet abstinence will be rewarded with up to EUR 100 per day.

Getting paid for doing nothing? That’s even more blatant than the idea of a basic income. Getting paid for doing nothing would be a complete reversal of today’s conditions. No more checking your Instagram feed, no more binge-watching your favorite series on Netflix, no more ordering anything from Amazon – completely out of the gigantic machine that has long since managed to turn even such user cultures into extractable labor, as the CAPTCHA case clearly shows.

Incidentally, absences from the workplace (“absenteeism”) are a common form of protest among workers who cannot or are not legally allowed to go on strike. There are many reasons for this in the Internet context: streaming platforms and other Internet-based services need servers and data centers to handle the traffic. The technical infrastructure for streaming services in particular consumes a considerable amount of energy. The energy consumption of the Internet produces roughly the same amount of CO2 per year as global air traffic.

Also, for many low-wage workers in digital knowledge production, it may be more lucrative to accept the daily 100-euro bonus than to fight for a job that is already being taken over, piece by piece, by AI language models.

Seizing the means of climate production here does not require an uprising, energy-sapping actions, or superhuman effort, but rather the consistent stubbornness of passive resistance. But here, too, the question arises as to who can afford to opt out of the digital world. Not only to give up entertainment, doomscrolling, or meme consumption, but also to negate digital visibility in the social environment, the maintenance of professional profiles and networks. Not to mention the benefits of bonus programs. Who can afford this absence of the Internet as a workplace – and this new form of privacy?

Universal basic income?

What would happen if the government simply paid every citizen a basic income? Wouldn’t that change the job market? A basic income is a regular, unconditional cash payment to everyone on an individual basis, without means testing or work requirements. In Berlin, there was an attempt to hold a referendum in 2022 on a pilot project for an unconditional basic income, but it failed to get the required number of signatures. Nevertheless, 125,000 citizens supported the “My Basic Income” team that initiated the referendum.

There are also different opinions and attitudes towards basic income. Some see the state as responsible, while others are trying to build basic income models based on digital tokens or community currencies, such as the Berlin-based cooperative Circles Coop, which provides a community-based means of payment for the exchange of everyday products and services based on the digital currency CRC. A growing network of Berlin-based business partners are involved, making it possible to shop at monthly markets or online via the Circles marketplace.

But can such projects help reorganize work? If so, how? One of the arguments often put forward is that a basic income could provide a secure financial base, help make the labor market more flexible and improve income security. A basic income could also create choices about the number of hours worked and allow individual care work to be integrated into working life in such a way that, for example, children can be looked after or relatives cared for without having to constantly torn themselves apart between the incompatible fronts of gainful employment and care work.

Despite all the apparent advantages, however, there is also fundamental criticism of basic income: Left-wing theorists argue that this approach does not go far enough, that it does not fundamentally challenge the neoliberal logic and only shifts the problem – accordingly they demand a universal basic outcome: vital services such as education, housing, food, health care, electricity, transportation, etc.

Economists, constitutional lawyers and politicians, on the other hand, warn of an incalculable cost risk and the creation of new inequalities through the watering-can principle of money distribution. The taz has presented the real political and economic contexts in connection with the constitutional necessities in the Federal Republic of Germany in all their complexity.

At the latest after these readings it becomes clear: Even if the referendum had received the necessary number of votes, the introduction of a basic income within our existing political and economic system would not be a no-brainer. So, if neither traditional employment, nor absenteeism, nor basic income protection can reform the labor market towards sustainability, how can we model the future of climate and work?

Organize work differently?

With the rise of the digital platform economy over the last fifteen years, a fundamental transformation of work and its means of production has taken place. New forms of employment have emerged on digital platforms such as Uber, Mechanical Turk or Deliveroo.

The Hans Böckler Foundation’s report “Working in the Digital Economy” refers to this form of employment as “digital day labor.”

Interest in cooperative Internet platforms was driven primarily by growing resistance to the sharing economy, which had used business models such as TaskRabbit to show that the new digital economy was not only leading to greater convenience and better deals, but also to increasing enslavement and precarization. By 2015, it became clear that digital apps had partially taken control of traditional labor markets. This new “work on demand” is accompanied by a loss of workers’ rights, social protection, and a blurring of the line between work and leisure.

In November 2015, the first international conference on platform cooperativism was held at the New School in New York. It laid the groundwork for an economic model in which successful platforms are copied and replicated cooperatively: Shared ownership, shared control, and collective protection of workers’ interests were at the core of this new business model.

Starting with platform monopolists like Uber, numerous local, self-managed car services emerged. Bicycle couriers began to band together and turn their backs on the large delivery services. Starting with Airbnb, Fairbnb emerged, a short-term accommodation service jointly organized by city councils and local committees. In this new cooperative digital economy, a collective of equal members organizes itself on the basis of cooperative structures.

Do “we” want that? Can “we” do it?

Work is organized collectively, workers have control over the means of production, such as software, and they agree on the company’s values and strategic goals in regular meetings. Increasingly, platform cooperatives are focusing their work on climate protection and how to act economically in the interest of the members, but at the same time radically in the interest of the environment.

It almost goes without saying that such cooperatives, which are not based on “cheap labor” or “cheap land,” can hardly be competitive in the global market. And yet this new economic culture holds the potential for the work of the future. At least if we want to shape the future as an alternative to the destructive status quo of capitalism. So we have to fight for it.

The big question is how to enable people to think and act together in cooperative structures. Ultimately, it is a matter of cultivating a cooperative “we,” of appropriating new principles and structures of shared governance. Indeed, reorganizing work is not just about inventing new organizational models, but about thinking about work from the needs of the collective and the environment. Conscious and sustainable climate production means creating and securing shared spaces where human and non-human work can take place in a balanced relationship based on mutual reproduction.

These spaces can be created in struggles. Struggles in which environmental and labor concerns are thought together and a new, cooperative “we” emerges. This is not a dream of the future. These struggles have been going on for a long time. I hope that my text will contribute to making them more visible and perhaps even more conscious.

Editor’s note: This text is a contribution to the Berliner Gazette’s “Allied Grounds” text series; the German version can be found here. For more content, visit the English-language “Allied Grounds” website. Take a look here: https://allied-grounds.berlinergazette.de